Essay 1 Declaration of Independence —The American Creed: Promise and Paradox

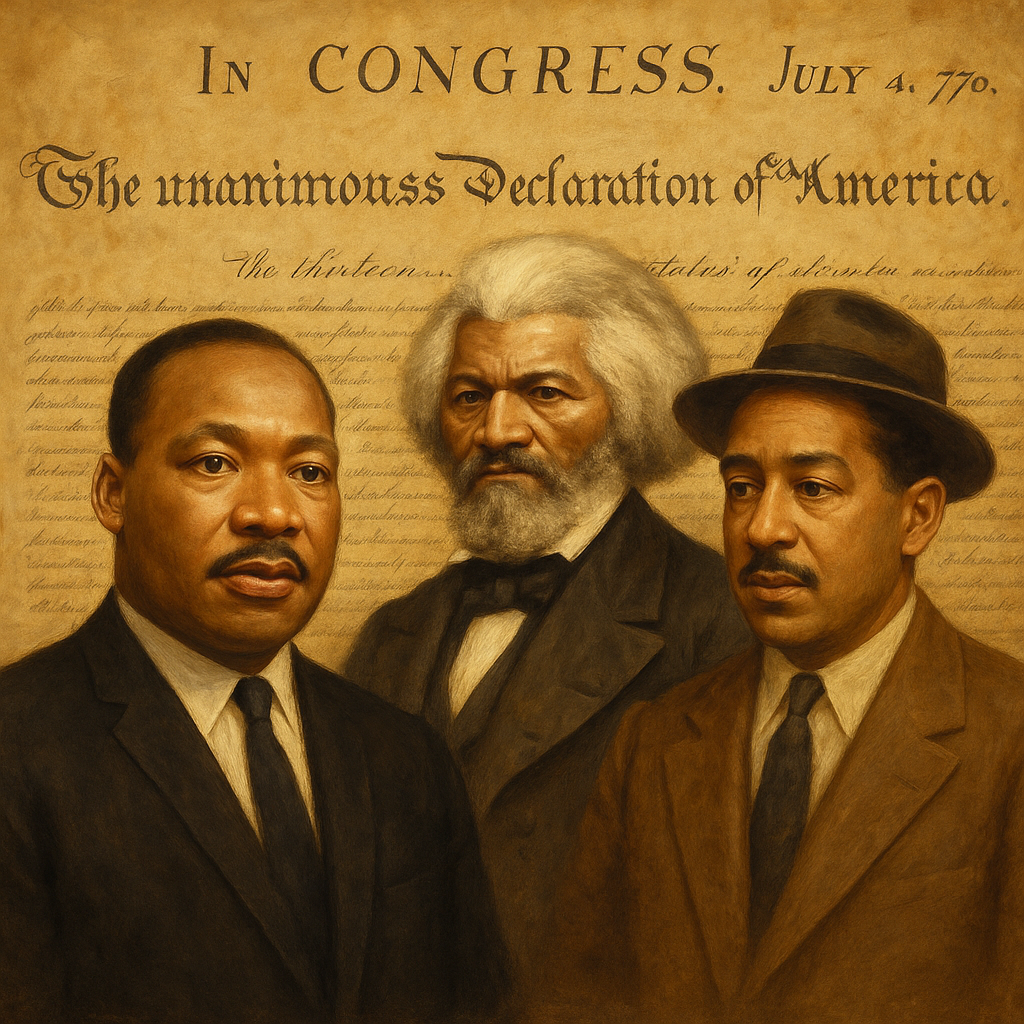

Regarding the picture, the backdrop is the Declaration of Independence and pictured from left to right are Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglass, and Langston Hughes.

This is the first of a year-long, 13 part series of essays based on the key principles of the Declaration of Independence that were written through the collective lenses of three famous Black icons: Frederick Douglass, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr, and poet Langston Hughes.

The series will end next 4th of July, the 250th anniversary of the birth of our country and the Declaration of Independence.

There will also be a concluding essay on how these icons might envision the Declaration being utilized to move forward through the next 250 years.

The inspiration for this series came from three local, Black female friends, Judy Toyer, Gaynelle Wethers, and Rev. Marilyn Cunningham. Judy provided the initial “nudge” as she did four years ago regarding the book I published, ‘Understanding and Combating Racism: My Path from Oblivious American to Evolving Activist’.

In self-reflection, this modest effort, based on my own life experiences in an attempt to open up oblivious white eyes like mine to the legacy and continuing racism in our country, barely dented the surface of this over 400-year scourge on our national consciousness and behavior.

So, my hope is that through utilizing the “eyes” of Frederick, Martin, and Langston, I am harkening back to the roots of my memoir in an attempt to again provide some enlightenment on what is possible fo us individually as well our country; and this time utilizing the fundamental principles of this country’s founding document at a very critical time in our history.

But my primary hope is that these essays demonstrate that progress towards justice is possible, even in the face of what appears to be overwhelming adversity. As Martin Luther King, Jr., is quoted in these essays, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Lastly, a significant attribution must be given to an important resource and research partner. Without the services of the AI app ‘Chat GPT’, this series would have been much more challenging to develop. I depended on the powerful capacity of “Chat” to help unravel and bring clarity to a project that would have added many more hours to not merely gather the perspectives of Douglass, MLK, and Hughes regarding the Declaration in the first place, but then to put together the nuances, context, and content in an orderly and understandable manner.

I was able to put aside any reservations I may have had about the accuracy of Chat’s research based on my own familiarity with the writings of the three authors as well as the Declaration of Independence. Additionally, my personal life experiences regarding racism and antiracism provided guidance that Chat’s conclusions were very coherent. This all said, I would appreciate any comments, questions, or challenges you may have regarding any of the essays.

Introduction

The story of the United States of America begins with a declaration—bold, poetic, defiant. In July 1776, representatives of thirteen colonies adopted the ‘Declaration of Independence’, proclaiming their break from the British Empire and justifying revolution in the name of universal human rights. The Declaration’s words have echoed across centuries, continents, and movements for freedom:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

This sentence is often called America’s creed. It is recited in schools, invoked in courtrooms, engraved on monuments. It has been used to justify war, inspire reform, and demand justice. It is so familiar that it can seem almost emptied of meaning—reduced to patriotic cliché.

But beneath its polished surface lies a paradox that has defined American history: a promise of universal equality proclaimed in a society that practiced slavery, dispossession, and exclusion. The very men who signed the Declaration excluded women from political life, denied rights to Native peoples, and held Black people in chains.

This contradiction was not a footnote; it was foundational. The American creed has always existed in tension between ideal and practice, promise and betrayal.

Yet this tension has also been a source of power. For more than two centuries, Americans have argued, fought, and sacrificed to close the gap between the nation’s stated ideals and its lived reality. The Declaration of Independence has been both a shield for the powerful and a weapon for the oppressed.

This first essay of a 13-part series examines that tension, focusing on the Declaration’s claim to be the founding statement of “The American Creed”. It explores how three visionary voices—Frederick Douglass (1852), Martin Luther King Jr. (1963), and Langston Hughes (1930s onward)—have read, critiqued, and reimagined this creed.

They did not dismiss the Declaration’s ideals. Instead, they treated them seriously—so seriously that they refused to let the nation forget them. They understood that to celebrate American independence without confronting its hypocrisy was to betray its promise.

By reading the Declaration of Independence through their eyes, we can see it more truthfully: not as a sacred relic, but as an ongoing challenge.

1. The Declaration’s Radical Claim

It is worth pausing over the radicalism of the Declaration’s core claim.

When Jefferson wrote that “all men are created equal,” he was rejecting the dominant political theory of his age: that power came from kings, by divine right. Instead, he insisted that power came from the people. Governments were not natural or inevitable; they were human constructions meant to secure rights.

“That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

This was the Enlightenment distilled into political language. It was not simply a call for independence from Britain. It was a statement of universal principles:

- Equality as a self-evident truth

- Unalienable rights belonging to all

- Government justified only by consent

- A duty to resist tyranny

It was revolutionary rhetoric. It inspired revolutions in France, Haiti, Latin America. It gave philosophical backbone to democratic movements around the world.

But from the start, the Declaration was marked by a contradiction so glaring that even some of its signers squirmed. Many of them owned enslaved people. “All men are created equal” did not mean all people. Women were excluded from citizenship. Indigenous nations were treated as obstacles to be conquered or displaced.

This tension—universal promise, narrow application—has been the central drama of American history.

2. The Creed and Its Critics

The phrase “The American Creed” is often used to describe the Declaration’s preamble. Political scientist Gunnar Myrdal called it “the moral basis of the American republic.” Abraham Lincoln described it as “a rebuke and a stumbling-block” to tyranny.

But the creed’s power depends on its meaning. Who is included in “all men”? Whose rights are unalienable? Who consents to be governed?

These are not theoretical questions. They have been matters of life and death.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, African American thinkers and activists returned to the Declaration again and again. They refused to abandon its principles. Instead, they used its own words to indict American hypocrisy and demand change.

Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and Langston Hughes are among the most powerful of these voices.

They did not agree on every detail. They wrote in different eras, faced different challenges, used different styles. But they shared a strategy: they treated the Declaration seriously.

They argued that if America truly believed its own creed, it would have to change.

3. Frederick Douglass: “This Fourth of July is Yours, Not Mine”

On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass stood before the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society and delivered one of the greatest speeches in American history: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Douglass was born into slavery, escaped to freedom, and became the era’s most electrifying abolitionist orator. He understood both the promise of the Declaration and the cruelty of its betrayal.

He began his speech by acknowledging the Founders’ courage. He praised their willingness to defy a king, to risk death for liberty. He did not deny the greatness of their act.

But then his tone shifted:

“This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

He called the celebration of freedom in a slaveholding nation a grotesque hypocrisy:

“Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today?”

Douglass laid out a searing indictment. While white Americans boasted of liberty, they bought and sold human beings. While they praised justice, they denied Black people even the most basic legal rights.

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.”

Yet Douglass did not reject the Declaration. He revered it:

“The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles.”

He argued that slavery was not consistent with American ideals—it was a betrayal of them. True patriots would abolish slavery, not celebrate it.

Douglass was both critic and believer. He used the Declaration’s language to shame the nation into change. He insisted that America’s true character lay not in its hypocrisy, but in its capacity for moral transformation.

4. The Right to Revolution

The Declaration does not only proclaim equality. It also proclaims the right of revolution:

“Whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it…”

This is not mild language. It justifies radical change when governments violate rights.

Douglass seized on this. He argued that abolition was not treason, but fidelity to American principles. If the government upheld slavery, it had forfeited its legitimacy.

“The Fourth of July is the first great fact in your nation’s history—the very ringbolt in the chain of your yet undeveloped destiny.”

He turned the Founders’ justification for independence against their descendants who defended slavery.

This appeal to the right of revolution is central to the American Creed. It insists that no government is above the people’s moral judgment.

5. Martin Luther King Jr.: “A Promissory Note”

More than a century after Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr. stood before a vast crowd at the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington. His “I Have a Dream” speech is one of the most famous in American history.

King directly invoked the Declaration of Independence:

“When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.”

He used the metaphor of a promissory note—a check written to all Americans, guaranteeing the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

But America, he said, had defaulted on that check:

“Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’”

Yet King refused to believe that the “bank of justice is bankrupt.”

He was not asking for anything new or radical. He was asking that America honor its own commitment:

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

Like Douglass, King treated the Declaration seriously. He saw it as a binding moral contract.

He also understood that naming American hypocrisy was not unpatriotic. On the contrary—it was the highest form of patriotism.

6. The Power of the Dream

King’s speech is often remembered for its poetic, visionary section—the repeated phrase “I have a dream.” But this vision was rooted in the Declaration’s promise.

King’s dream was not fantasy; it was an ethical demand. He insisted that America must rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed.

He spoke of children joining hands across racial lines, of justice rolling down like waters. These images were not decorative flourishes. They were expressions of what America claimed to be at its core.

By using the language of the Declaration, King transformed it. He made it impossible to hear “all men are created equal” without thinking of the country’s racial caste system.

Yet he refused to give up on the phrase. Like Douglass, he believed the Declaration’s ideals were worth fighting for.

7. Langston Hughes: “Let America Be America Again”

While Douglass and King delivered speeches meant to stir crowds, Langston Hughes crafted poetry meant to haunt the national conscience.

In his poem “Let America Be America Again,” written during the 1930s, Hughes gave voice to those excluded from the American promise.

“Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

… America never was America to me.”

This is no simple denunciation. The poem’s power comes from its tension between critique and hope. Hughes refuses to lie about America’s failures.

“I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart.

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek.”

He creates a chorus of voices who have been promised freedom but delivered oppression.

But Hughes does not end in despair. He demands that America become what it claims:

“O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!”

Here is the essence of the American Creed as challenge. Hughes insists that the dream is not dead—but that it has not yet been achieved. He claims it as the right of all who have been denied it.

8. The Tension of Promise and Hypocrisy

What unites Douglass, King, and Hughes is their understanding of the tension in the American Creed.

They knew that the Declaration’s words had been used to justify conquest and exclusion. But they also saw that those same words contained the seeds of a better future.

They refused to surrender the founding promise to those who betrayed it.

For them, the Declaration was not simply a historical document. It was an unfinished project.

Douglass challenged America to abolish slavery as proof of its belief in equality.

King demanded civil rights legislation as the payment of a moral debt.

Hughes demanded economic and racial justice as the fulfillment of a deferred dream.

Their critiques were searing because they took America’s own words seriously.

9. Patriotism as Dissent

Too often, American culture treats criticism as disloyalty. “Love it or leave it” is the familiar taunt.

But Douglass, King, and Hughes model a different form of patriotism: one rooted in dissent.

They loved America enough to tell it the truth.

They recognized that true patriotism is not blind celebration of a country’s myths, but commitment to its best principles.

They forced the nation to see that real loyalty sometimes means demanding change.

10. The Universal Claim

The Declaration’s language is powerful precisely because it is universal.

“All men are created equal.”

Jefferson may have meant it narrowly. But its words could not be contained.

They have been claimed by abolitionists, suffragists, labor organizers, civil rights activists, LGBTQ advocates, immigrant rights defenders.

This universality is both the source of the Declaration’s power and the cause of its deepest conflicts.

To say “all” and mean “some” is hypocrisy. But to say “all” and fight to mean “all” is justice.

Douglass, King, and Hughes demanded the latter.

11. A Living Document

Some see the Declaration as a historical artifact—important in 1776, irrelevant today.

But it was never meant to be a static formula. It was written as a revolutionary text.

It does not merely describe the world; it declares a moral standard. It is an invitation—perhaps a demand—to judge any government by whether it respects equality and rights.

This is why Douglass, King, and Hughes turned to it. They treated it as a living document that still had work to do.

By doing so, they challenged Americans to keep working too.

12. The American Creed as an Ongoing Challenge

So what is the American Creed today?

It is not simply the words of 1776, frozen in time. It is the ongoing struggle to make those words true for everyone.

It is the recognition that equality and rights are not gifts handed down by the powerful, but claims demanded by the people.

It is the understanding that government requires consent—but that true consent depends on justice.

It is the duty to challenge tyranny, whether foreign or domestic.

And it is the acceptance that the work is never finished.

Conclusion: The Work Ahead

Frederick Douglass, in 1852, forced America to confront its hypocrisy. Yet he also held up the Declaration’s principles as “saving principles,” worth fighting for.

Martin Luther King Jr., in 1963, called on America to cash the check it had written, to live out the true meaning of its creed.

Langston Hughes, across decades, reminded America that it had never been what it promised—but that it could be.

Together, they show that the American Creed is not a finished fact but a moral demand.

To recite “all men are created equal” is easy. To make it real is hard.

It requires honesty about history. It requires recognizing whose rights have been denied. It requires listening to those who have been excluded. It requires changing institutions, laws, and hearts.

And it requires never giving up on the promise.

Because if America means anything, it means the belief that all people are equal in dignity and rights, and that government exists to protect that equality.

That belief is not owned by any party, region, or generation. It is a legacy and a responsibility.

We honor Douglass, King, and Hughes not by celebrating them as heroes safely in the past, but by continuing the work they demanded: holding America to its word.

The Declaration of Independence is not simply the story of what America was in 1776. It is a map of what America must still become.

August 1, 2025 1:54 pm /

In my opinion, your best work yet. We all must heed the words of the leaders of the oppressed in order to claim freedom for all. Great job doing that. I know the latest middle class generation in their 20’s and 30’s are intolerant of bigotry an any form. Your essay would stand well with them.

August 1, 2025 5:16 pm /

Many thanks, Ted. Coming from a fellow author, former clssmate and great friend really means a lot. It will be interesting to see where this series takes me and this important discussion…. Bill