Essay 4, Declaration of Independence — Consent of the Governed: The Moral Foundation of Legitimate Power

Before proceeding into this month’s essay, I would like to share some personal reflections.

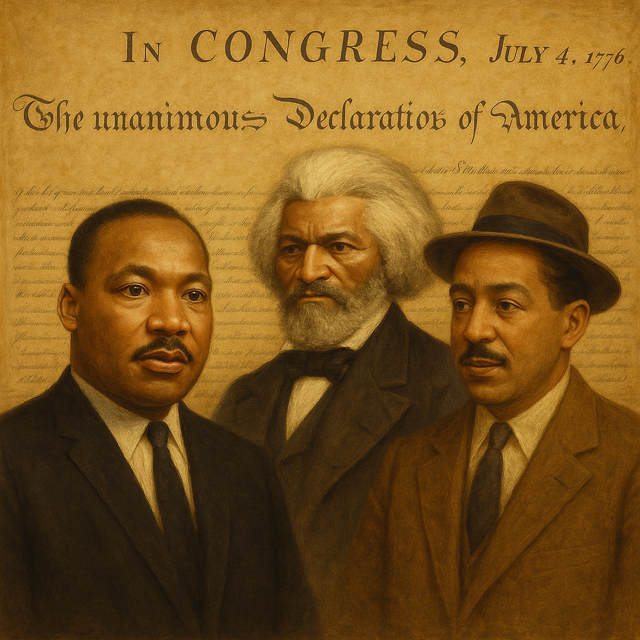

At the conclusion of the essay, it states: “Their (Douglass, King, Hughes) challenge is our inheritance. “Consent of the governed” is not a gift the powerful grant the people. It is a right the people must claim—and keep claiming. It is not a settled fact but an ongoing project. It is, in the words of the Declaration itself, a right and a duty to make government serve the people’s freedom, rights, dignity, and equality. Because only then will government be truly just.”

The recent and second “No Kings” nationwide protest on October 18th at almost 3000 locations involving over seven million people is a distinct representation of our government requiring our consent regarding its leadership. And the Trump regime is failing miserably in providing any governing leadership … with focused intentionality to instead subvert and crush our “freedom, rights, dignity, and equality” as dictators and kings do. The “consent of the governed” remains the ongoing test of American democracy (see Section XIV) and is portrayed vividly through the powerful voices of Douglass, King, and Hughes in this essay.

Per the Declaration, Patriotism demands dissent! And as author, famous icon, and critical observer of our country, James Baldwin, once said: “I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Who might be some of today’s “voices” who bring critique, insight, wisdom, articulation, and passion regarding the movement to thwart the existential threats our country is enduring today due to “Trump 2.0” and Project 2025?

The MOVEMENT of “No Kings” I believe requires “soul” oriented leaders, visionaries, and thought creators. I welcome any names you might think should be considered and who warrant our full-throttled support to assist in the development of a “Civil Rights” type Movement which was so successful decades ago.

A final thought: a series like this of thirteen essays is prone to have some repetition. But I look at any repetition as reinforcement of the principles and values we desperately need to be burned into our psyches … like the revolutionary fervor of 250 years ago which led to the creation of this great country … and all built upon the foundation of dissent against a monarchical, authoritative government … then and now.

With radical resilience, “No Kings” forever!!

- Introduction: Power, Legitimacy, and the People

When the Declaration of Independence set out to justify revolution against Britain, it did so with a striking claim about the nature of government:

“That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

This phrase does more than denounce a particular monarch. It asserts a universal principle: No government is legitimate unless it rests on the consent of the people it governs.

In an era of kings, emperors, and inherited authority, this was revolutionary. It argued that power is not natural, divine, or self-justifying. Instead, power is conditional—a trust granted by the governed to those who rule.

But like the other principles of the Declaration, the claim to government by consent was fraught with contradiction. In 1776, consent was narrowly defined—reserved for white male property owners. Millions within the colonies had no voice or vote. Enslaved people were treated as property. Indigenous nations were denied sovereignty. Women were excluded entirely.

Still, the power of the phrase endured. Over the centuries, movements for abolition, suffrage, civil rights, labor rights, and decolonization would seize upon it. “Consent of the governed” became not only a founding principle but a rallying cry for expanding democracy and dismantling oppression.

This essay explores the idea of consent of the governed in theory and practice. It asks: Who gets to consent? How is that consent expressed? What happens when consent is denied or forced?

We will see how Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and Langston Hughes each challenged America to live up to this ideal—not by abandoning it, but by demanding its true realization.

II. The Enlightenment Background: Government by Agreement

The Declaration’s claim that government derives “just powers” from consent was heavily influenced by Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke, who wrote:

“Men being by nature all free, equal, and independent, no one can be put out of this estate, and subjected to the political power of another, without his own consent.”

In Locke’s vision, government arises from a social contract. People agree to form a government to protect their rights. Government’s authority is legitimate only so long as it honors that agreement. If it fails, the people have the right to alter or abolish it.

This idea rejected the “divine right of kings” that had justified monarchical rule for centuries. It laid the groundwork for constitutionalism, representative democracy, and revolution.

But in practice, “consent” was often defined narrowly. Property requirements, racial exclusions, and gender barriers limited who counted as “the people.” The American Revolution itself left many unrepresented even as it claimed to fight “taxation without representation.”

The promise of consent was universal in theory but partial in reality—a contradiction that would shape American history.

III. The Founding Contradiction: Consent and Slavery

Nowhere was this contradiction sharper than in the coexistence of democratic ideals and human enslavement. Enslaved people had no legal personhood, let alone political voice. They were ruled entirely without their consent.

This was not a hidden flaw; it was foundational. The Constitution’s compromises on slavery (the Three-Fifths Clause, the Fugitive Slave Clause) enshrined a system in which the governed could not consent, and the unconsenting were not even fully counted.

The Founders’ language about consent became both an inspiration and an indictment. Abolitionists would repeatedly point out this hypocrisy, arguing that the United States could not claim to respect “consent of the governed” while maintaining slavery.

IV. Frederick Douglass: Whose Consent?

Frederick Douglass was one of the sharpest voices exposing this hypocrisy. In speeches and writings throughout his life, Douglass asked America to confront a basic question:

“How can you speak of government by consent when millions are enslaved?”

In his 1852 speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, Douglass rejected the idea that American government was legitimate while it denied liberty to so many:

“You invite me to celebrate the Fourth of July? … This Fourth of July is yours, not mine.”

Douglass saw clearly that the claim to government by consent was not just incomplete but fraudulent if it excluded the enslaved. Yet, crucially, he did not dismiss the ideal. Instead, he embraced it as a moral standard.

He believed that true democracy required expanding the meaning of consent:

- Ending slavery

- Enfranchising Black Americans

- Recognizing the full personhood of all

For Douglass, the legitimacy of government rested on universal participation. Anything less was tyranny disguised as freedom.

V. Consent and Resistance: The Right of Revolution

The Declaration’s logic is clear:

“Whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it.”

Consent is not passive. It includes the right to withdraw it. When government betrays its purpose, revolution is justified.

Douglass seized on this. He argued that abolition was not disloyal—it was the highest form of patriotism. The enslaved were justified in resisting their condition by any means necessary because they had never given their consent to be ruled in bondage.

This argument echoed through the abolitionist movement. It transformed the idea of consent from a dry theory into a call for radical change.

VI. Post-Emancipation: Consent Without Power

The end of slavery did not immediately mean real consent for Black Americans. The Reconstruction Amendments abolished slavery (13th), granted citizenship (14th), and voting rights (15th). Yet by the late 19th century, these gains were systematically dismantled.

Jim Crow laws, voter suppression, racial terror, and disenfranchisement denied Black people meaningful participation in government. Consent of the governed became a hollow phrase when Black citizens were barred from voting, segregated from public life, and subject to racist violence.

The principle remained powerful in theory but was betrayed in practice.

VII. Martin Luther King Jr.: Democracy Deferred

Nearly a century after the Civil War, Martin Luther King Jr. made the principle of consent central to the Civil Rights Movement.

In the 1950s and 60s, Southern states maintained segregation through law, intimidation, and violence. Black citizens faced poll taxes, literacy tests, and outright terror designed to suppress their vote.

King understood that denying the vote was not just an inconvenience but an attack on the very foundation of democracy. Without the vote, there is no consent. Without consent, there is no legitimate government.

In his 1957 “Give Us the Ballot” speech, King said:

“Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights.”

He argued that access to the ballot box was the key to unlocking all other rights.

In his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King also addressed those who valued “order” over justice. He argued that unjust laws—those that excluded people from political participation—had no moral authority:

“One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

King linked consent to justice. A law that excludes people from meaningful participation is not consented to—it is imposed.

VIII. Voting Rights: The Test of Consent

King’s emphasis on voting was not abstract. It was rooted in the understanding that consent of the governed is expressed through the vote.

Without free and fair elections, consent is a fiction.

The struggle for voting rights has been one of the central battles to fulfill the Declaration’s promise.

- The 15th Amendment (1870) promised no racial discrimination in voting.

- The 19th Amendment (1920) extended voting rights to women.

- The Voting Rights Act of 1965 attacked literacy tests and other forms of disenfranchisement.

But these gains were never secure. After the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, states passed new laws restricting voting access. Voter ID laws, purges of voter rolls, reduced polling places—all disproportionately affected poor, Black, and minority voters.

The struggle over voting rights is the modern expression of the fight over consent. As King warned, democracy is fragile when participation is restricted.

IX. Langston Hughes: Whose Voice Counts?

Langston Hughes gave poetic expression to the frustrations of those denied consent.

In “Let America Be America Again,” Hughes names the many who have never had a say in how they are governed:

“I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek—

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.”

Hughes does not limit his critique to Black oppression. He speaks for all who have been ruled without real voice.

His poetry asks: Who counts? Who belongs? Whose voice matters?

Hughes’s vision of democracy is radical precisely because it insists on a universal inclusion. He does not abandon the American dream of government by consent. He demands it be made real:

“O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!”

Consent of the governed, for Hughes, is a promise waiting to be kept.

X. Consent and Economic Power

While the Declaration focuses on political consent, economic inequality has always undermined real democracy.

Frederick Douglass knew that freedom without economic power was a cruel joke. After emancipation, Black Americans were denied land, credit, and fair wages. Sharecropping and debt peonage replaced slavery with another system of domination.

Martin Luther King Jr. saw this clearly in his final years. He understood that formal political rights meant little without economic security:

“What good is having the right to sit at a lunch counter if you can’t afford to buy a hamburger?”

King’s Poor People’s Campaign aimed to expand the meaning of consent to include economic justice.

Without fair wages, education, healthcare, and housing, people cannot meaningfully participate in self-government. Economic desperation limits freedom of choice.

Langston Hughes also captured this truth in verse. In “Ballad of the Landlord,” the tenant’s protest against a slumlord is met with police violence and prison:

“Landlord, landlord,

My roof has sprung a leak. …

Police! Police!

Come and get this man!”

The poem reveals the gap between formal rights and lived reality. Consent is hollow when people are economically coerced.

XI. Consent and Coercion

Consent must be free to be meaningful. But throughout American history, consent has often been forced or manipulated.

- Enslaved people were denied any say in their own lives.

- Native peoples were coerced into ceding land through unequal treaties and violence.

- Workers faced blacklists and violence for organizing unions.

- Immigrants were exploited for cheap labor while excluded from political power.

- Women were subjected to legal and economic dependency that limited their choices.

These forms of coercion reveal that government by consent cannot be reduced to voting alone. It requires dismantling systems of domination that distort choice.

True consent requires the conditions for freedom: education, security, health, and opportunity.

XII. The Expansion of Consent

Despite these barriers, the history of the United States is also a history of expanding consent.

- Abolitionists fought to make the country confront slavery’s denial of human consent.

- Suffragists argued that “consent of the governed” was impossible without women’s votes.

- Civil rights activists exposed the lie of democracy under Jim Crow.

- Immigrants fought for naturalization and citizenship rights.

- Indigenous activists demanded sovereignty and self-determination.

Each movement took the Declaration’s promise seriously—often more seriously than the nation itself.

They recognized that democracy is not self-executing. It requires constant struggle to ensure that all have a real voice.

XIII. The Fragility of Consent

Even as voting rights expanded, threats to consent remained. Gerrymandering, voter suppression, disinformation campaigns, and corporate money in politics all distort the people’s will — and this all unfortunately continues to this day.

Frederick Douglass warned that “power concedes nothing without a demand.”

Martin Luther King Jr. reminded us that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice” only if people bend it.

Langston Hughes spoke for generations whose consent was demanded without ever being honored.

Their message is clear: Consent is not a static achievement but a continual demand.

XIV. Consent and the Right to Dissent

Consent of the governed also implies the right to withdraw consent—to protest, dissent, and resist injustice.

The Declaration itself is a revolutionary document. It justified rebellion against a government that violated rights.

Frederick Douglass celebrated this legacy while reminding Americans that the enslaved were fully justified in seeking their own freedom.

Martin Luther King Jr. practiced nonviolent civil disobedience, recognizing that breaking unjust laws is an expression of moral dissent.

“An unjust law is no law at all.”

Langston Hughes gave voice to those who refused to accept false promises, even as they refused to give up hope.

Consent of the governed does not mean blind obedience. It requires a public willing to question, critique, and even disrupt the status quo in the name of justice as in the current “No Kings” protests.

XV. Consent in a Diverse Society

America today is vastly more diverse than in 1776. Consent of the governed now means navigating differences of race, religion, culture, and ideology.

True consent cannot mean domination of one group over another. It requires institutions that respect pluralism and protect minority rights.

It requires a civic culture that values dialogue, disagreement, and compromise without demanding uniformity.

Douglass, King, and Hughes all modeled the kind of moral clarity and inclusive vision that a diverse democracy needs. They refused to reduce justice to the majority’s whim. They insisted on universal principles.

XVI. The Work Ahead

Consent of the governed remains the test of American democracy.

It demands:

- Free and fair elections accessible to all.

- Protection against voter suppression and disenfranchisement.

- Honest representation uncorrupted by money or manipulation.

- Civic education that prepares citizens to participate thoughtfully.

- Economic conditions that allow genuine freedom of choice.

- Respect for dissent and protest as part of democratic life.

These are not partisan demands. They are requirements for legitimacy.

To claim government by consent while denying people’s voice is to lie. To fulfill the promise of consent is to ensure that every person counts.

XVII. Conclusion: A Continuing Revolution

The Declaration of Independence called the colonies to rebel against a king who ruled without their consent. But it also laid down a principle that would forever challenge America itself:

- Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.

- Frederick Douglass asked America to confront the hypocrisy of proclaiming consent while enslaving millions.

- Martin Luther King Jr. demanded that America honor the promise of the vote and dismantle systems of racial exclusion.

- Langston Hughes spoke for all who had been denied a voice, insisting that America must become what it claimed to be.

It is not a settled fact but an ongoing project.

It is, in the words of the Declaration itself, a right and a duty to make government serve the people’s freedom, rights dignity, and equality.

Because only then will government be truly just.