Declaration of Independence… Essay #6: “Safety and Happiness”

As quoted below, this latest essay in the series outlines how “the Declaration is not only asserting rights but defining government’s purpose: to secure the people’s safety and happiness.”

I would like to call your attention to two personal observations regarding this statement. First, that the voices of Douglass, King, and Hughes resonate profoundly and powerfully today; e.g.,“each of them saw that true safety and happiness require confronting entrenched power, redistributing resources, and democratizing decision-making.” How true considering the current wrecking ball of the Trump regime destroying our basic rights and freedoms such as ‘due process’ to name just one of many.

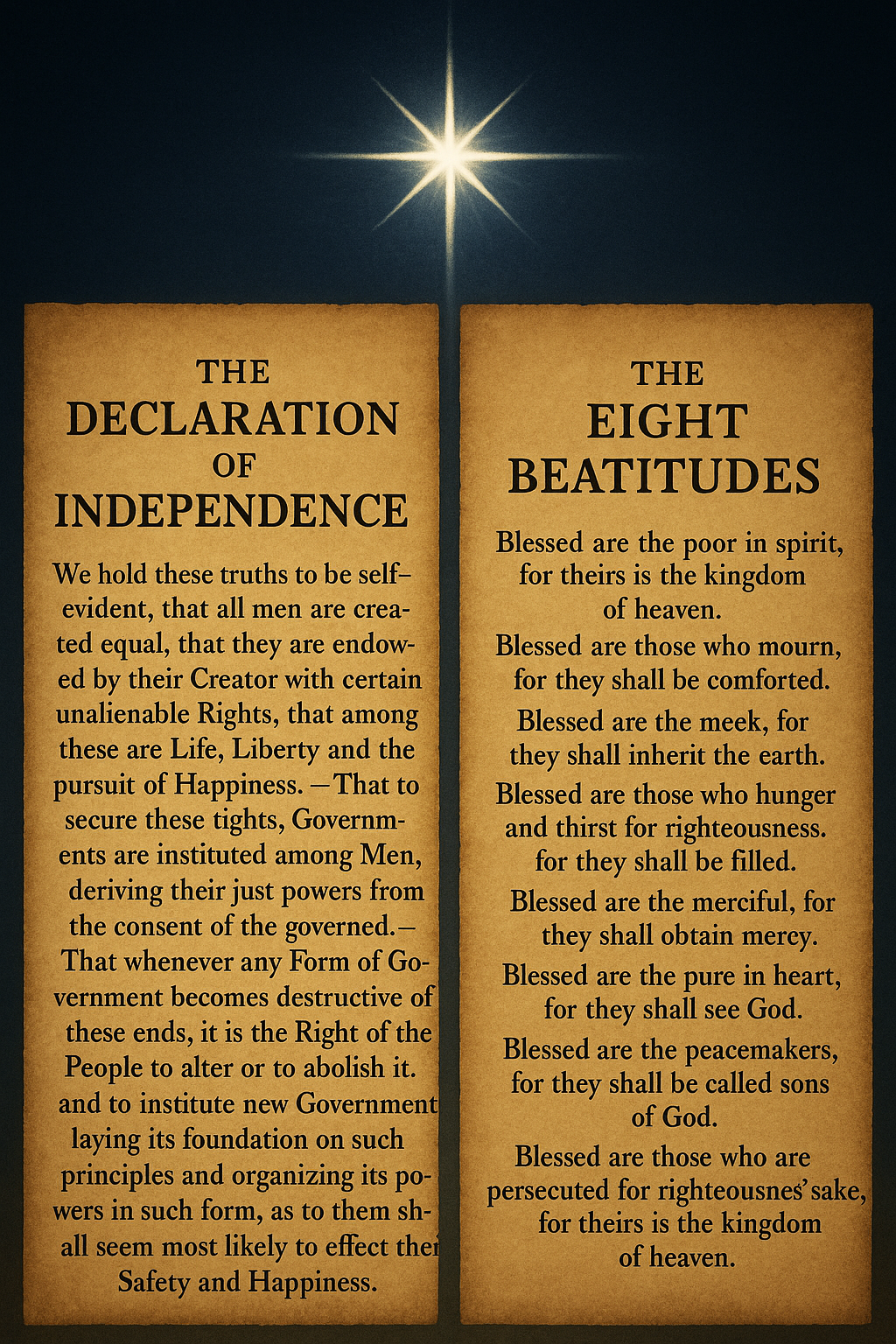

My second observation goes to an even higher level and captured in the above picture. This entire essay I believe is replete in its mirroring at a much higher order towards our one true King and the Kingdom of God. How appropriate a thought given the recent birth celebration of God’s presence in our world as a human and alive in all things. Approximately thirty-three years after Jesus’ birth, He presented to the world the ‘Eight Beatitudes.’

When (hopefully!) you read this essay, try to reflect upon the Declaration’s words in the context of the Beatitudes and I think you will see what I mean. Also, please note the presence of the star of Christmas shining gloriously in the picture above both texts.

The Declaration of Independence is therefore a distinctly moral document and provided enlightenment for its time and a vision for the future given its endurance almost 250 years later and counting.

It is much deeper than simply a pronouncement of “No Kings” and provides many opportunities for a “heart conversion” like the Beatitudes do towards the Kingdom of God, the one and only true King. As just one example of this in the essay, there is MLK’s vision “… of the Beloved Community required ending racism, poverty, and war.” Clearly a Beatitudes-like statement.

(See https://share.google/aimode/sM6t7kJKEfRPbWElo for more details comparing these sacred texts).

The MAGA political longing for the alleged “comfort of the past” (at least for the White majority) is distinctly out of alignment with both the Declaration and the Beatitudes. We must move forward towards the “better” in the context of the sacred words of both these text as portrayed by our three icons. But who can help us today towards the fulfillment of their vision?

I first offer you an Old Testament example of a “soul leader” for his time (and ours) , the prophet Jonah (please see https://email.cac.org/t/d-e-sulditt-tlkrtkjkyd-w/). Secondly, I suggest that Pope Leo is today’s presence of a “soul leader” in the Jonah vintage and hopefully he will inspire more of us to speak truth to power and uplift the respective dialogue, outlook, and conversation to higher ground. In this way we will connect the dots to the Declaration’s “Safety and Happiness” resolution as well as to the Beloved Community and the Kingdom of God! Happy New year!

Two final and repeated notes: there will be some repetition from previous essays and I hope readers will see that more as reinforcement versus annoyance. Secondly, a continued shout out to my resource partner, CHAT GPT, for its contributions with each of these essays.

The Pursuit of Safety and Happiness: The Moral Purpose of Government

I. Introduction: The Forgotten Clause

When people quote the Declaration of Independence, they often stop at “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” But there’s another crucial line—often overlooked yet essential:

“…laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

This is not a vague platitude. It’s a moral standard for judging legitimacy.

A government exists not to perpetuate its own power, enrich a privileged few, or maintain a static order. It exists to serve the people’s well-being.

If it fails to protect their safety or promote their happiness, the people have the right to reform or replace it.

This principle is as radical as the others in the Declaration. It demands that political institutions be judged by their impact on real human lives. It roots the abstract rights of liberty and equality in the tangible conditions of security and flourishing.

But as with other founding ideals, “safety and happiness” was proclaimed in a society that denied both to many.

Enslaved people were forced to live in terror and deprivation.

Indigenous nations faced displacement, violence, and cultural destruction.

Women lacked legal independence and bodily autonomy.

Poor and working people endured precarity without protections.

The phrase “safety and happiness” thus became not just a promise but an indictment.

Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and Langston Hughes each seized on this gap. They demanded that America make good on its promise, insisting that safety and happiness are rights for all, not privileges for some.

II. The Enlightenment Background: Well-Being as Political Purpose

The idea that government exists to secure safety and happiness was not new in 1776. It drew from Enlightenment thought, especially John Locke’s vision of a social contract.

Philosopher John Locke argued that people enter civil society to protect their lives, liberties, and estates. Government is a means, not an end.

Thomas Jefferson adapted this idea, replacing “estate” with the more aspirational “pursuit of happiness.”

But the Declaration’s language goes even further. It asserts that governments should be organized in whatever way is “most likely” to secure these ends.

This is a pragmatic, experimental, even democratic approach. It rejects fixed hierarchies or divine rights.

It says the people themselves must judge what government best serves their needs.

But Enlightenment thinkers often excluded many from this promise. Women, the poor, people of color were rarely seen as equal participants in this social contract.

The Declaration’s words were universal in theory but partial in practice.

III. The Founding Contradiction: Whose Safety? Whose Happiness?

From the start, the promise of safety and happiness was unequally distributed.

For white colonists, revolution was justified to protect their rights. But for enslaved Africans, “safety” meant constant surveillance, brutal punishment, and family separation.

For Indigenous nations, colonial “safety” required their displacement and destruction. Settlers’ happiness was built on their dispossession.

The U.S. Constitution itself was drafted to “ensure domestic tranquility”—but also contained clauses protecting slavery.

In this context, “safety and happiness” became an alibi for oppression. It justified order for some by imposing violence on others.

This contradiction would haunt American history, forcing each generation to ask: whose safety? whose happiness? at whose expense?

IV. Frederick Douglass: Denied Safety, Demanding Happiness

Frederick Douglass understood this hypocrisy firsthand.

Enslaved people were denied all security except the security of their masters’ property rights. Their happiness was dismissed as irrelevant.

In his famous 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, Douglass exposed the cruelty of celebrating liberty in a land of bondage:

“Your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery! … To him, your celebration is a sham.”

He described the terror of the lash, the constant threat of being sold away from family. For the enslaved, there was no safety.

Douglass argued that true safety and happiness required abolition. It was not enough to talk of natural rights in the abstract. Those rights had to be enforced in law and reality.

He also challenged the idea that “order” justified oppression. Slaveholders claimed to maintain safety—by terrorizing the enslaved. Douglass called this false peace:

“There can be no peace where there is no justice.”

For Douglass, securing safety and happiness for all demanded the end of systems that denied humanity.

V. Post-Emancipation: The Promise and the Betrayal

After emancipation, Black Americans expected that the government would secure their safety and happiness.

The Reconstruction Amendments promised citizenship, equal protection, and voting rights.

But this promise was quickly betrayed.

Black Codes criminalized Black freedom.

Sharecropping and debt peonage recreated economic dependency.

White supremacist terror—including lynching—made safety a distant hope.

The federal government withdrew protection in 1877, abandoning Black citizens to Jim Crow.

Douglass, late in life, condemned these betrayals. He argued that without protection from violence and deprivation, Black freedom was a cruel joke.

The failure to secure safety and happiness for all citizens revealed the limits of American democracy.

VI. Martin Luther King Jr.: Safety and Happiness as Civil Rights

Almost a century after Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr. picked up this demand.

The Jim Crow system enforced a false “order” at the expense of Black safety and happiness.

Segregated schools and facilities enforced second-class citizenship.

Economic discrimination kept Black families in poverty.

Police brutality enforced racial hierarchies.

Voting restrictions silenced Black political voice.

King understood that civil rights were not just about abstract equality but about real well-being.

In his “I Have a Dream” speech, he said:

“We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.”

He linked freedom to tangible security:

“No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

King rejected any “peace” that was simply the absence of conflict without justice:

“True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice.”

For King, government had a moral obligation to secure not only liberty in the abstract but the conditions for people to live safely and happily.

VII. The Promissory Note: Safety and Happiness as Unfulfilled Debt

In his “I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King Jr. famously described the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution as a promissory note:

“a promise that all men, yes, Black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

But America had defaulted on that check.

For King, the struggle for civil rights was a demand for payment on that debt. The “pursuit of happiness” was not an idle phrase. It demanded equality before the law, economic opportunity, freedom from violence.

King rejected any comfort in gradualism or moderation. He insisted that the time was “now” to make real the promise of safety and happiness for Black Americans.

He also recognized that injustice anywhere threatened safety everywhere:

“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.”

This vision went beyond Black freedom. It demanded that the nation reorder its priorities to ensure security and well-being for all.

VIII. Langston Hughes: Whose Happiness?

Langston Hughes gave poetic voice to those left out of America’s promise.

In “Let America Be America Again,” he wrote:

“Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed—

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.”

Hughes did not reject the dream of America. He condemned its betrayal.

He named those excluded from safety and happiness:

“I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek—

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.”

His poetry insisted on expanding the moral circle to include workers, immigrants, the oppressed.

For Hughes, “safety and happiness” was not a private luxury but a collective obligation.

He warned that denying people this promise bred anger, resistance—even revolution:

“What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up … or does it explode?”

IX. Economic Justice as Safety and Happiness

Both King and Hughes understood that formal rights were hollow without economic justice.

King’s final years focused on poverty and inequality. In his 1967 speech, “Where Do We Go From Here?,” he declared:

“We must honestly face the fact that the movement must address itself to the question of restructuring the whole of American society.”

King’s Poor People’s Campaign demanded:

- A living wage

- Decent housing

- Education

- Healthcare

He knew that safety and happiness required more than freedom from legal discrimination. It required freedom from want.

Langston Hughes, too, chronicled economic struggle. In “Ballad of the Landlord,” he showed how poverty undermined any sense of security:

“Landlord, landlord,

My roof has sprung a leak.”

When the tenant protests, the system responds with eviction and jail, not justice.

Their critique reveals that government cannot claim legitimacy if it protects property over people, profit over well-being.

X. Structural Violence: The Hidden Threat to Safety

King spoke not only of direct violence but of structural violence:

“A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual doom.”

He condemned racism, poverty, and militarism as interlinked systems that denied people safety and happiness.

Police brutality was not an accident but part of enforcing an unjust order.

Economic inequality was not a failing of individual effort but a product of exploitation.

War abroad drained resources and moral authority at home.

King’s insight was that true safety is not built on suppression but on justice.

As long as these structures remained, the promise of safety and happiness was a lie.

XI. The Politics of Fear: Perverting Safety

Historically, appeals to “safety” have often been used to justify oppression.

Slaveholders claimed they needed violence to keep order.

Jim Crow laws were defended as preserving “public safety.”

Police crackdowns on protest were called “law and order.”

Anti-immigrant hysteria was framed as protecting American jobs and culture.

Such uses of “safety” reveal how the concept can be twisted to serve power.

King warned against this:

“We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.”

Douglass, too, exposed false peace that rested on injustice:

“Where justice is denied … neither persons nor property will be safe.”

Langston Hughes’s poetry insisted on naming the violence done in the name of order.

True safety cannot mean the security of some built on the oppression of others.

XII. Democratic Participation: The Foundation of Safety and Happiness

The Declaration says governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Consent is not just a procedural formality. It is the means by which people shape government to secure their safety and happiness.

But throughout American history, participation was restricted:

- Enslaved people had no voice

- Women were denied the vote

- Black voters were disenfranchised through violence and law

- Poor people were excluded by poll taxes and literacy tests

- Gerrymandering and voter suppression persist today

King’s struggle for voting rights was a fight to make the promise of safety and happiness real.

Without democratic voice, people cannot hold government accountable to its purpose.

XIII. The Right to Dissent: Safeguarding Safety and Happiness

Government’s obligation to secure safety and happiness also requires protecting dissent.

Frederick Douglass warned that power concedes nothing without a demand.

King practiced civil disobedience as a form of moral revolution. He understood that dissent was not a threat to order but its necessary correction:

“Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

Langston Hughes used poetry as protest, amplifying the voices of the marginalized.

True safety and happiness depend on the ability to challenge injustice without fear of repression.

XIV. Safety and Happiness as Collective Goods

The Declaration speaks of “their Safety and Happiness”—not merely the individual’s private gain, but the people’s shared well-being.

This is a collective vision of good government.

Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and Langston Hughes all understood that safety and happiness cannot be secured in isolation:

- Douglass demanded not just his own freedom, but abolition for all

- King’s vision of the Beloved Community required ending racism, poverty, and war

- Hughes wrote of the common struggle of workers, immigrants, and the poor

This idea challenges rugged individualism. It says our well-being is bound up with our neighbors’.

If some are unsafe—policed, incarcerated, brutalized—none can be truly secure.

If some are denied happiness—oppressed, exploited, marginalized—none can fully flourish.

XV. Beyond Minimal Survival: Flourishing as Political Aim

“Safety and Happiness” is not merely survival or absence of danger. It is the chance to flourish.

Martin Luther King Jr. understood this deeply. He rejected the idea that civil rights victories were enough without economic justice.

“What good is having the right to sit at a lunch counter if you can’t afford to buy a hamburger?”

He envisioned a society where basic needs were met:

- Decent housing

- A living wage

- Access to education

- Quality healthcare

Langston Hughes imagined an America where all could dream freely, without fear or want.

Their vision expands safety from mere policing to genuine security—from the mere right to be left alone to the right to live well.

XVI. Structural Change: Organizing Government for Safety and Happiness

The Declaration says governments should be organized in whatever form is “most likely” to secure safety and happiness.

This is an invitation to rethink institutions.

Frederick Douglass pressed the nation to end slavery and create laws protecting Black rights.

King called for a radical restructuring of society, including:

- Ending segregation

- Expanding voting rights

- Investing in anti-poverty programs

- Challenging militarism

Langston Hughes envisioned a more egalitarian nation where the worker’s voice mattered as much as the boss’s.

XVII. The Tension Between Order and Justice

Throughout American history, those in power have invoked “order” to suppress demands for justice.

Slave patrols enforced “order” on plantations.

Segregationists claimed to maintain “peace” by denying Black rights.

Police broke strikes in the name of “safety.”

Modern surveillance and anti-protest laws target dissenters.

But as Douglass, King, and Hughes knew, order without justice is oppression in disguise.

True safety and happiness come not from suppressing unrest but from addressing its causes:

- Economic inequality

- Racial injustice

- Political disenfranchisement

- Social exclusion

King warned:

“A riot is the language of the unheard.”

He did not excuse violence but understood its roots. His answer was not repression but justice.

XVIII. America’s Ongoing Struggle

The promise of safety and happiness remains unfulfilled.

Black Americans continue to face disproportionate violence from police.

Economic inequality leaves millions in precarity.

Healthcare is often inaccessible.

Housing is unaffordable in many places.

Climate change threatens the safety of entire communities.

In these struggles, Douglass, King, and Hughes’s insights remain urgent.

They teach that the legitimacy of government rests on its ability to secure real well-being for all.

They remind us that America’s greatness is not in its wealth or military might but in its capacity to deliver freedom from fear and want.

XIX. The Moral Obligation to Act

The Declaration does not merely assert that people may change their government if it fails. It says they have a right and a duty.

This duty remains ours.

We cannot simply accept a society where:

- Some live in fear of violence

- Many cannot afford healthcare

- Children go hungry

- Voting rights are suppressed

- Immigrants are demonized

If government fails to secure safety and happiness for all, it must be changed—through organizing, protest, legislation, democratic participation.

This duty is not one of destruction but of renewal. It is the ongoing work of building a just society.

XX. Conclusion: The Radical Promise

“Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

This sentence is not a relic of 1776. It is a living moral demand.

It calls us to judge all institutions by whether they secure our safety and happiness.

It demands that we resist any order that preserves privilege at the cost of justice.

Frederick Douglass claimed this promise for the enslaved.

Martin Luther King Jr. claimed it for the oppressed and poor.

Langston Hughes claimed it for all denied the dream of America.

Their legacy is an invitation—and a command—to continue this work.

For the promise of safety and happiness is not just a goal to be reached but a principle to be fought for, again and again, until it is true for all.